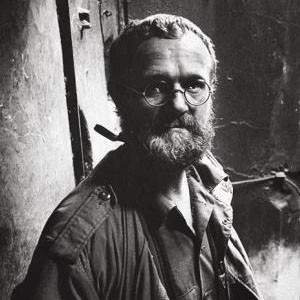

Interview: Frank Horvat with Josef Koudelka.

.jpg)

First interview, January 1987

Frank Horvat : You ask if I have made good use of my vision. I believe I have used it too little. Photographers like Henri (Cartier-Bresson) always have a camera with them and are looking all the time. I don’t know how to do that. Right now, for example, I am not looking, my mind is occupied by words.

Joseph Koudelka : What do you mean by “I am not looking”?

Frank Horvat : I am not looking with the idea to make a photograph.

Joseph Koudelka : How are you looking?

Frank Horvat : I am seeing only a few of things around me. Only those that I want to see.

Joseph Koudelka : But to see what you want to see, you have to look. And to choose..

Frank Horvat : It seems to me that, to see “photographically”, I have to prepare myself in advance. Possibly for a long time. For instance it would be difficult for me, on my way out from here, to make photos of Paris. To see, I would have to go to another city, say to New York, live in a hotel room by myself and start walking through the streets, at first without a camera. And little by little I would begin to see. In the same way, I wouldn’t know how to make a portrait of a woman, just off the hip. I would have to think about her, to imagine her. She would have to prepare herself or to be prepared with someone’s help. And even then, when I would eventually be facing her, with my camera, I might not feel ready. It could take me two or three hours to understand her, little by little, through the viewfinder.

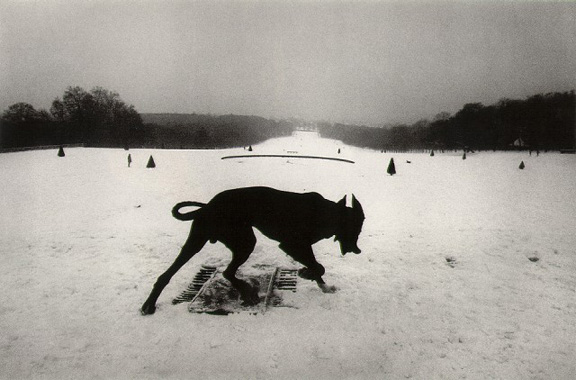

Joseph Koudelka : Perhaps because you want to understand. Me, I do not try to understand. For me, the most beautiful thing is to wake up, to go out, and to look. At everything. Without anyone telling me “You should look at this or that.” I look at everything and I try to find what interests me, because when I set out, I don’t yet know what will interest me. Sometimes I photograph things that others would find stupid, but with which I can play around. Henri as well says that before meeting a person, or seeing a country, he has to prepare himself. Not me, I try to react to what comes up. Afterwards, I may come back to it, perhaps every year, ten years in a row, and I will end by understanding.

Frank Horvat : You prepare yourself in your way. I imagine that when you find a subject that interests you, your photo is, in a way, already prepared within you. As if you had set up a place into which it fits.

Joseph Koudelka : What’s “my photo”?

Frank Horvat : Your photos often are recognizable, which is to say that they have something in common. Maybe the space between the figures, and the tensions within that space.

Joseph Koudelka : I don’t know. But I interrupted you, you were speaking about yourself.

Frank Horvat : If I have used my eyes well? I fear not having used my time well.

Joseph Koudelka : That is the gist of my question. Your time, not only your eyes.

Frank Horvat : Look, I met you in person only about an hour ago, though I am familiar with your photos and I remember a few things that I have been told about you. If I had to express the idea that I have of you, in a single sentence, I would say “He lives out of a sleeping bag.” That would sum up your way of using your time, which is different from mine, and probably more efficient. It’s not that I am dissatisfied with my own life. But I know that too often I have done things that didn’t really interest me, or that distracted me from what I thought was my real purpose, because I forced myself to respond to the ideas or the desires of others. I believe that if I was allowed to move back and to relive some hours of my life, the moments I would choose would be those when I was photographing for myself, in the streets of New York or in India. Or even some moments in the studio, when making portraits.

Joseph Koudelka : Personally, I have had the good fortune of always being able to do what I wanted, never working for others. Maybe it is a silly principle, but the idea that no one can buy me is important for me. I refuse assignments, even for projects that I have decided to do anyhow. It is somewhat the same with my books. When my first book, the one on the gypsies, was published, it was hard for me to accept the idea that I could no longer choose the people to whom I would show my photos, that any one could buy them.

Frank Horvat : What are your points of reference – I mean in literature, in painting, in music?

Joseph Koudelka : There are a few things that I like very much, but that I do not practice. I have always played music, and I would like to listen to it more than I do, but I don’t have the opportunity, due to the lack of time and place. When I was a kid, I did a lot of reading, then a little less during my studies, and hardly any since I left Czechoslovakia – always for the same reason, because I do not have a place of my own. When I travel, I don’t even know where I am going to sleep, I don’t think of the place where I will lie down until the moment I roll out my sleeping bag. It’s a rule that I’ve set for myself. Because I told myself that I must be able to sleep anywhere, since sleep is important. In the summer I often sleep outdoors. I stop working when there is no more light, and I start again in the early morning. I do not feel this to be a sacrifice, it would be a sacrifice to live otherwise. As for my points of reference, I don’t know what they would be.

Frank Horvat : But, in the world, what seems important to you?

Joseph Koudelka : Questions about the world are difficult for me. I mistrust words. I come from a system where words have no value. I got used to not listening much to what people say. Or rather, I listen to them, but I give less importance to what they say, than to the way in which they say it. When someone declares: “I am a communist”, (or a socialist, or an anarchist), that means nothing to me. What counts is what people do.

Frank Horvat : But what else counts for you? Is it important that your photos be preserved after your death?

Joseph Koudelka : It never seemed important to me that my photos be published. It’s important that I take them. There were periods where I didn’t have money, and I would imagine that someone would come to me and say: “Here is money, you can go do your photography, but you must not show it.” I would have accepted right away. On the other hand, if someone had come to me saying: “Here is money to do your photography, but after your death it must be destroyed”, I would have refused. Do you understand?

Frank Horvat : What matters is that the photos exist.

Joseph Koudelka : Absolutely. Not that they be published or that people admire me. To be known can even be a nuisance. I don’t like to feel like the center of attention. I often travel to a horse market in the north of England, where I know just about everyone. When they see me they ask: “Your book, when does it come out? I will never see it, I will be dead before then.” And it may be true, some are dead already. But I can always bring to a son the photo of his father, to an old man the photo of when he was not so old. What counts is that the work exists. Besides, I am not someone who likes his own photos very much.

Frank Horvat : But I have been told that you put them on the wall to see if you can live with them.

Joseph Koudelka : I did that in Czechoslovakia, and I would do it again if I had a home. I lived all the time with the photos of the gypsies. If you live all the time with a thing, and you go on looking at it, you end up either by getting tired of it, or by being sure that it satisfies you. For me a good photo is one that I can live with. It’s like living with good music or a good person.

Frank Horvat : Maybe because photography is made essentially of time. I often think that what we show is a point in time, more than a window onto space.

Joseph Koudelka : The philosophic aspects of photography don’t interest me. What interests me are its limits. I always photograph the same people, the same situations, because I want to know the limits of those people, of those situations, and also my own limits. It’s not so important that I succeed in making a photo the first time, nor the fifth, nor the tenth.

Frank Horvat : I know that when you were photographing the gypsies you often went back to the same places, to the homes of the same families.

Joseph Koudelka : I had a specific circuit, where I found the same type of situation again and again. It is what I still try to do, but now it’s gotten more complicated. I have neither a car, nor even a driver’s license, though I hope to get them. When one works as I do, health problems can become a limitation. Some years ago, I suffered from back pains and the doctor told me: “That comes from your lifestyle.” So I took care of myself and recovered, but I know that there will be a time when I will no longer be able to live as I do. When I was thirty, I kept telling myself that at forty a photographer is finished. Possibly this was only to force myself to take advantage of my time. Now I am almost fifty. I still make some good photos and I hope to carry on. But I believe that the truly creative periods are those when you live with intensity. If you lose intensity, you lose everything.

Frank Horvat : But is it a matter of age? The portraits of women, that I made these last years, are perhaps the project into which I have put the most intensity.

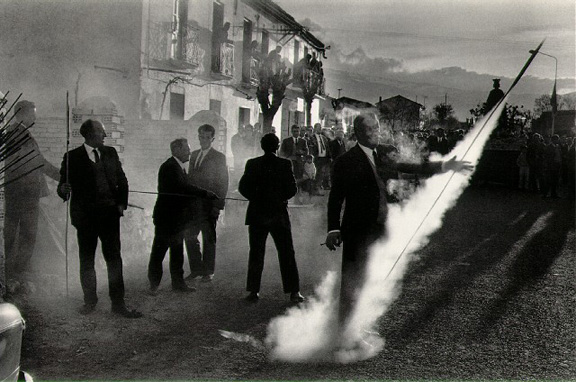

Joseph Koudelka : For me, there are few portraits that I truly admire. One time, a funny thing happened : I was near Rome with a pilgrimage of gypsies from Yugoslavia, organized by some Catholic priests. Not actually priests, but some kind of laymen, they earned their living and were nice people. In talking with me, they found out that I was the author of the book about gypsies. They told me that they had a copy of it and that they had cut out the pages, to put them up on the walls of a shack that they used for a chapel. And under each photo the gypsies wrote the name of someone they knew.

Frank Horvat : They knew the actual people that you had photographed?

Joseph Koudelka : No, they knew others, in Yugoslavia, who resembled them. “We know you very well” they said to me, “we call you Iconar”. That reminded me of something that I had said to Henri, one of the first times we met, and that made him really laugh: I said that rather than a photographer, I was a collector of photos.

Frank Horvat : Is that your reason for always going back to the same places?

Joseph Koudelka : It’s the reason why photography was easier in the beginning. It’s like a dart game: at the beginning, you can toss them anywhere, they will always be well placed. Wherever you hit is the right place ( in English in the original). But once you start building something, you realize that certain pieces are missing.

Frank Horvat : So, when you return to those same places, it’s with the idea of completing a series, of which some pieces are still missing?

Joseph Koudelka : I have a general idea. But as I cannot go everywhere, I limit myself to a few countries in Europe that I feel are close to my way of being: like Spain, Ireland, Italy, Greece. I often return there and I hope to continue returning until I will feel sure of having reached the limits of my possibilities. But I would rather not talk about projects.

Frank Horvat : Will this work be as important as what you did in Czechoslovakia?

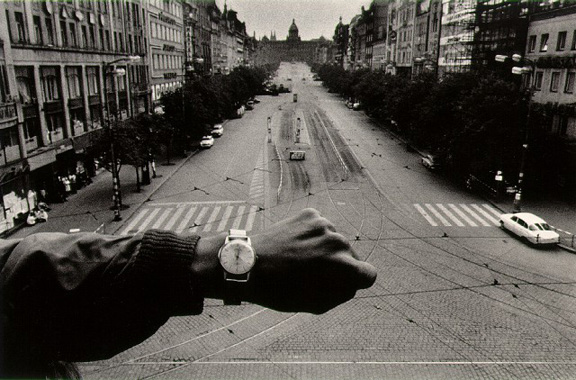

Joseph Koudelka : I don’t know what’s important to the people who look at my photos. What’s important to me is to make them. I work all the time, but there are only a few of my photos that I find really good. I am not even sure that I am really a good photographer. I think that anyone working as I do could do the same. But my purpose is not to prove my talent. I photograph almost every day, except when it’s too cold for traveling the way I do – as in this time of winter. Sometimes my photos are OK, other times they are not, but I think that eventually something will come out of my work. I don’t worry about it. I also take photos of my own life, such as those at the beginning of the small paperback book: of my feet, of my watch. When I am tired I lie down, and if I feel like photographing and there is nobody around me, I photograph my own feet. They are not great photos, some people dislike them. For a similar reason, I always photograph the places where I sleep, and the interiors where I spend some time. It’s a rule that I have given to myself, because these are things that one forgets. Maybe one day I’ll make a book with them, nothing but those little photos. It may upset some people who know me only as the photographer of gypsies, and who don’t want to see me any other way. But I don’t care about what people think, I don’t try to change people. Nor to change the world.

Second interview, March 1987

Frank Horvat : You said that you were not very happy with our first interview. I re-read the text, and also I re-read my earlier interviews with other photographers. This made me realize that in the course of these meetings, I partly lost sight of my initial purpose, which was to talk about photography, rather than about photographers. Nonetheless, I would like to begin with a personal comment. I know several people who consider you somehow as their conscience. I know that you are not trying to play the role of guru, but it is your severity toward yourself which leads other people to look at themselves with less indulgence.

Joseph Koudelka : You say I am a conscience. That’s the last thing I want to be. It sounds as if I judge others, as if I feel superior. I have only been lucky. Because, at the beginning, I was an aeronautical engineer and was able to do photography without the need to be paid. Later, I continued to be lucky, by having the opportunity to work for eighteen years, without having to accept even a single assignment. But this is no reason to make anyone feel at fault, because my way of doing photography is only one among many – and perhaps not even the best.

Frank Horvat : I would like to see some prints of your work, for example some from the last year, that you said were not quite satisfying to you. And I would like you to explain why.

Joseph Koudelka : I don’t see any reason for doing that. If I am dissatisfied, it’s simply because good photos are few and far between. A good photo is a miracle.

Frank Horvat : But it may be is easier to explain why a photo is not so good, than to explain why it’s good.

Joseph Koudelka : But what if almost all are bad? For you, making photos is different, you like to direct. In my case, all depend on what happens, I have to find a situation that interests me. That is why I keep coming back to the same places. But often what I expect doesn’t happen, or it happens without my being able to make a good photo.

Frank Horvat : But what do you mean by “good”?

Joseph Koudelka : “Good” is when a situation is at its maximum, and when I myself am at my maximum. It may happen that I reach that maximum the very first time, by chance, and that I return to the place another ten times, over ten years, without being able to do any better. Or that in looking for a certain maximum I find something else, that I hadn’t imagined. What matters is my search, my motivation to go further. But I can not sell this way of working to a magazine, I can’t expect them to send me ten times to Lourdes, and to have me come back with some photo that has nothing to do with Lourdes!

Frank Horvat : Was the Prague Spring a maximum? It certainly was an event for which you couldn’t prepare yourself and that had little chance of happening again.

Joseph Koudelka : It has been the maximum of my life. In ten days, everything that could happen in my life did happen. I was at my own maximum, in a situation at its maximum. That may have been the reason why I “covered” it better than all those professional reporters, who had come from all over the world. I wasn’t even a photo journalist. Someone – who in fact knew me rather well – had written about me that I could succeed in any kind of photography, except reportage.

Frank Horvat : Were you aware of it being a maximum, while you were living it? Did you tell yourself every morning: “These days are my maximum, too bad if they cost my life?”

Joseph Koudelka : I wasn’t thinking about danger. Later, some people who had seen me in front of the tanks said that I could have been killed. But I never thought of that. Even though in ordinary life I am far from brave.

Frank Horvat : Actually, I was mistaken in saying that you were not prepared: the work that you had done during the ten preceding years had been a kind of preparation. Without that work, you wouldn’t have been able to photograph the Prague Spring as you did.

Joseph Koudelka : Certainly not. But I do not agree with what that person had written about me. I don’t care what people think, I know well enough who I am. But I refuse to become a slave to their ideas. When you stay in the same place for a certain time, people put you in a box and expect you to stay there.

Frank Horvat : What seems important to me, is that during those days you knew precisely how to see, because you had spent the ten preceding years in training your vision.

Joseph Koudelka : I agree with that. But I don’t pretend to be an intellectual or a philosopher. I just look.

Frank Horvat : And you spend your life looking and saying “yes” or “no” to what you see, by releasing or not releasing the shutter, by choosing or not choosing a contact. It is like the binary system of computers, except with many more a “no” than a “yes”. What seems interesting to me, are the ten years of “yes” and “no” that prepared you to make, at the moment of the Prague Spring, photographs that others didn’t make. Even though the events were the same for all.

Joseph Koudelka : Another reason was that I hadn’t been parachuted into Prague, like the rest. I was a Czechoslovakian, I was photographing in the country whose language I spoke, whose problems were my own problems. And I was working for myself. Too often people with some talent go where there is some money to be made. They begin to trade a bit of their talent for a bit of money, then a little more, and finally they have nothing left to themselves. In Czechoslovakia we didn’t have many freedoms, and particularly not the freedom to make money. But that led us to choose professions that we really loved. I always photographed with the idea that no one would be interested in my photos, that no one would pay me, that if I did something I only did it for myself.

Frank Horvat : I understand. But what seems the most important to me is what you just said about the maximum. Someone else might have made a few well composed photographs, from behind a tree, and then gone home. You went forward, to search further. Because you had a certain idea of that maximum.

Joseph Koudelka : The maximum was in the air. I knew that all the things that could happen in my life were happening. There was a girl I kept running into all the time. At first I was suspicious of her, I imagined KGB spies everywhere. Then that girl approached me, opened her bag and said : “I meet you all the time, you must not have eaten for three days.” So I fell in love with her. Everything that could happen did happen. I met all the people whose existence I had imagined. The power of the situation was so great, that it created all those possibilities.

Frank Horvat : Yes, but if you had not been prepared by the work of the ten preceding years, the situation might have brought you the same intensity, the same love story, but not the same photos.

Joseph Koudelka : That comes from my way of working. After having seen my contacts, I do not only print the good photos, but all those that seem to me of some interest, even if I know that they are botched. And I keep looking at them, so as to integrate that experience into my system. Now I can almost photograph without looking through the viewfinder, I have mastered it so well, that it’s almost as if I were looking through it. What I want is to find a passage from the unconscious to the conscious. When I photograph, I do not think much. If you looked at my contacts you would ask yourself: “What is this guy doing?” But I keep working with my contacts and with my prints, I look at them all the time. I believe that the result of this work stays in me and at the moment of photographing it comes out, without my thinking of it.

Frank Horvat : Like a computer program. You spend a lot of time preparing your program, so that at a given moment, in front of a very complex situation, that program permits you to react instantly and correctly.

Joseph Koudelka : I would have liked to show you a kind of catalog that I made ten years ago, where I classified my photos according to their composition. If there is something that you like and that you are interested in, and if, in addition, you have some ability and a little energy to spend, it’s bound to work. The program will function. But what is important, afterwards, is to leave the program behind and to move ahead. It would be too easy to let yourself become a prisoner of what you have built, to let the results come out automatically. At some point, one must destroy the program, and start a new one from scratch.

Frank Horvat : Yes. When I was doing my essay on trees, I realized that as my work was proceeding, my program would get more and more precise, to the point that in the end it became a limitation, making me do the same photographs over and over!

Joseph Koudelka : I am not interested in repetition. I don’t want to reach the point from where I wouldn’t know how to go further. It’s good to set limits for oneself, but there comes a moment when we must destroy what we have constructed.

Frank Horvat : I agree that we should change the program, but I believe that there are some principles that we shouldn’t touch.

Joseph Koudelka : Which principles?

Frank Horvat : If only I knew! If I do these interviews, it is precisely to find out. One principle could be to always aim for a maximum, as you say. I know photographers who have given up on that. They do a good job, showing what they choose to show, and what indeed is the representation of some reality, but to me that is not enough.

Joseph Koudelka : And why do you think some people give up searching for the maximum?

Frank Horvat : I only know one answer, which scares me: because they don’t have enough energy left.

Joseph Koudelka : That scares me, too. We already talked about it in our first meeting, and I told you that the limit could be around forty. It happens to all of us.

Frank Horvat : On the other hand, Titian made some of his best paintings at eighty. And so did Renoir, Rodin, Picasso. But painting may be a different matter…

Joseph Koudelka : Possibly. It’s also true that Kertesz made some beautiful photos in his last years – but those were not the kind of photos we are talking about, which demand a certain physical fitness, if only to seek out the situations. It seems to me that in painting there is less difference between a masterpiece and a work that is not altogether a masterpiece. Or at least less difference than in photography: because in painting technique is more important.

Frank Horvat : Whereas photography depends on the intensity of the moment. I have great admiration for people like Munkasci, who worked with large format cameras, which allowed them to make only one photo in a given situation. He could never give himself a second chance.

Joseph Koudelka : You may be right. But I am the product of a different era. If I couldn’t shoot lots of photos, I would not be the photographer that I am. Still, the cost of film has often been a problem. At times, to save money, I had to work with remainders of movie-film, and even to buy film that was stolen. But when I have only three rolls of film left in my bag, I panic.

Frank Horvat : I understand that. Sometimes I shoot fifteen rolls in two hours, just for a studio portrait. But that does not keep me from feeling that each sitting is a unique event, which can never be repeated.

Joseph Koudelka : When I wake up in the morning, and I feel good, I tell myself: “Today may be the last day of my life.” That is my sense of urgency. But I keep wondering about what you just said, that I am a conscience. People have told me that. People much younger than myself have told me: “I would like to work as you do.”

Frank Horvat : Only they don’t.

Joseph Koudelka : Perhaps because they have an idea of me that doesn’t correspond to reality. When I left Czechoslovakia, I used to live on milk, bread and potatoes. It became something I was known for. So much that once, at the home of some friends in Holland, whom I was visiting, they put in front of me a plate of potatoes, while they treated themselves to goulash. I don’t want to be the slave of my legend!

Frank Horvat : You refuse to be the slave of money, the slave of your legend… Are you the slave of something?

Joseph Koudelka : I am the slave of my mind. I travel alone, I sleep outdoors. Even when I get a lift in someone’s car, I separate myself from that person in the morning, and only join up again in the evening. When I arrived in the West, I didn’t speak the local languages, so even when I had the money I didn’t know how to get served in a restaurant. I’m still unable to write French, I feel like an immigrant worker. I have spent much of my time by myself, with the result that I’m stuck with certain ideas, that may not always fit with reality. I am the slave of these ideas.

Frank Horvat : But don’t you think that the real slavery is the one that we choose? Being a slave to money, as I am, is to some extent the result of a choice. The limits of your mind may be something that you have chosen.

Joseph Koudelka : I was born with this mind. It comes from someone who was there before me. But in a certain sense, I chose to be as I am, and it is to this degree that I do not feel it as slavery. It may seem slavery to others, who see me from outside-but for me it’s freedom. Which doesn’t mean that it couldn’t change: now I’m the father of a little girl, and I have to earn money like everyone else. I am fifty years old, it’s the time of reckoning. I have done what I wanted, now I have to make good use of the time and energy that are left. Look: all these files contain my contact sheets – which doesn’t mean that they contain many good photos, only that I have done a lot of work. It will take years to really look at all that. Even if I fall ill, or if I am immobilized for some other reason, there is plenty of work to be done.